I play a lot of deckbuilders. Don’t you? They’re great. I want to talk about an overlooked subgenre of deckbuilding which I think is pretty neat, but that’s sadly somewhat rare: “set-based” deckbuilders.

Or that’s what I’m calling them in my head anyway. I don’t think there’s a name for any of this, so let me invent a taxonomy real quick: In most deckbuilders, you build a deck one card at a time. Let’s call that “Singleton” deckbuilding. That’s in contrast to adding cards in groups, or “Set-Based” Deckbuilding.

Singleton Deck Construction

Most all deckbuilders are about adding and removing single cards from a deck. That is, one of the main decisions the player is going to be making is about picking a single card to add to their deck (or not).

This is totally normal and expected, so much so it hardly bears noticing. But having gameplay revolve around individual cards in this way actually has some particular qualities if you think about it:

- It’s high friction, because the player will need to make many such decisions; they’re constructing a full deck where every card (or every card after some starting set) is being added one by one.

- Those decisions need to be spread out, so this really lends itself to making deck changes over time, not all at once.

- There’s a lot for the player to keep track of. Because the deck you’re playing with is constantly changing in composition, the player has to remember and reassess their cards somewhat frequently.

- The cards themselves generally need to be reasonably balanced against all other cards (or at least, all other cards of their type or rarity, etc). Because if they aren’t, then the choice of whether to add one or not would be too easy.

- You generally need to allow pruning from the deck, to help the player filter out bad cards they’ve added or started with, or cards that ended up not being useful because of subsequent decisions in drafting.

- The player will need to evaluate each card individually, so there’s an upper limit on how complex any given card can be.

- Because of the selection process (choosing one and not choosing others), the player will be seeing a lot of cards they don’t immediately play with. As a consequence, the game needs a high quantity of viable cards even if the player isn’t immediately using them.

Not an exhaustive list by any means. These aren’t good or bad qualities, they’re just things that naturally inhere in the way this mechanic works, which pushes the overall design of the game in certain directions. Nor are they required; any given game might embrace or push against any of these. But the structure of the mechanic lends itself to certain designs over others.

So, singleton drafting lends itself to a particular kind of deckbuilding game: One with a large (but balanced) card pool, which is used to slowly construct a deck over the course of the game.

But obviously there’s another way to do it, which would be to add cards in groups. That is, cards come in fixed sets, and are added or removed from your deck in those groups. Let’s take a look at what that can look like.

Examples of Set-based Deckbuilding

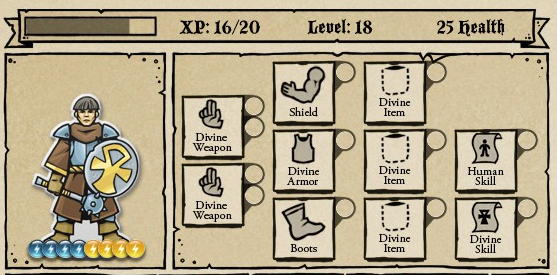

So in Card Quest (2017), one of my favorite games, you construct your 17 card deck before a run, but you don’t select the cards individually. Instead, you pick them in sets that come in four groups:

- 6 cards related to your subclass

- 5 cards for your weapon

- 4 cards for your off-hand

- and, 2 utility cards which every deck gets

Each of those main slots has a few different options to choose from. So instead of choosing 17 cards out of 100, or whatever, you’re choosing between this set of 6 and that set of 6, and so on.

So in that weapon slot you can equip a Broadsword, and it’ll give you 2 Slice cards, and 3 Slash cards. Or, you could equip a dagger, and get 2 Backstab cards, and 3 Jabs:

You still need to get a handle on each card individually, and you need to think about these will work with the cards you’re choosing in the other sets. But you don’t need to try and collect “Jab” cards to set up the “Backstab” you drafted. There’s already a bit of synergy in the set.

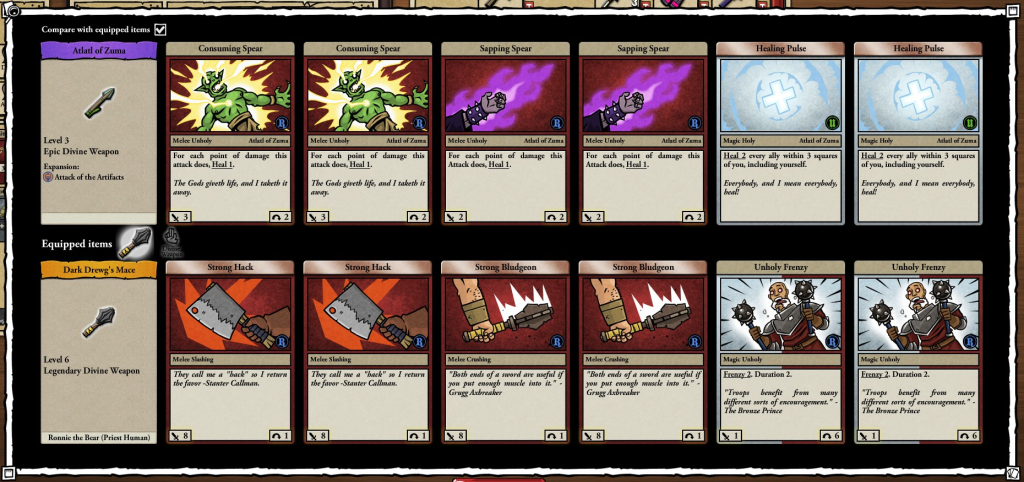

A paper-doll inventory is a really effective metaphor for this “cards come in sets” idea, so it’s by far the most common expression of this mechanic. The first game I saw using this was Card Hunter (2013). It’s a grid-based tactics game, where you have a party of three characters, each with their own 36 card deck. Each equipment slot they have can hold an item which will contribute 3 cards to that deck (and 6 from each weapon):

The slots dictate the kind of cards there, so Boots (which any class can equip) will typically give you movement or dodging cards, but only Clerics can equip the “Divine Item”, which gives you three clerical magic cards. There is a huge quantity of items in the game, so the deckbuilding can get very granular. But you’re still only modifying your deck in these discrete chunks of cards, so a comparison of two weapons becomes a comparison of its underlying set. Here’s a spear that gives you some health drain and minor healing, versus a club with direct damage and buffing:

There’s a similar system in Trials of Fire (2021) too, where equipping items determines the deck used in the tactics portion. Most games with set-based deckbuilding tend to have it as separate phase that comes before other gameplay, and after which the deck isn’t modified further during play itself. But it doesn’t necessarily have to work that way, and you can see an example of that in Deep Sky Derelicts (2018), which uses a “roguelike deckbuilder” formula where the deck is modified on the fly during the game, but in the form of finding equipment that grants sets of cards to your deck:

“Set-based” deckbuilding doesn’t need an equipment slot metaphor, it’s just a very convenient pattern for it. There are games that don’t use it though, especially if it’s being splashed in to a game that doesn’t otherwise use sets. Like Monster Train (2020) is primarily about singleton deckbuilding, but some special events present you with opportunities to get a set of cards together (typically, some bad cards to offset a good one). Or maybe in Nowhere Prophet (2019) your ‘convoy deck’ is edited over the game, but at the beginning it has a base set of cards you choose upfront, and there’s so many different options it kind of feels like a set-based mechanic.

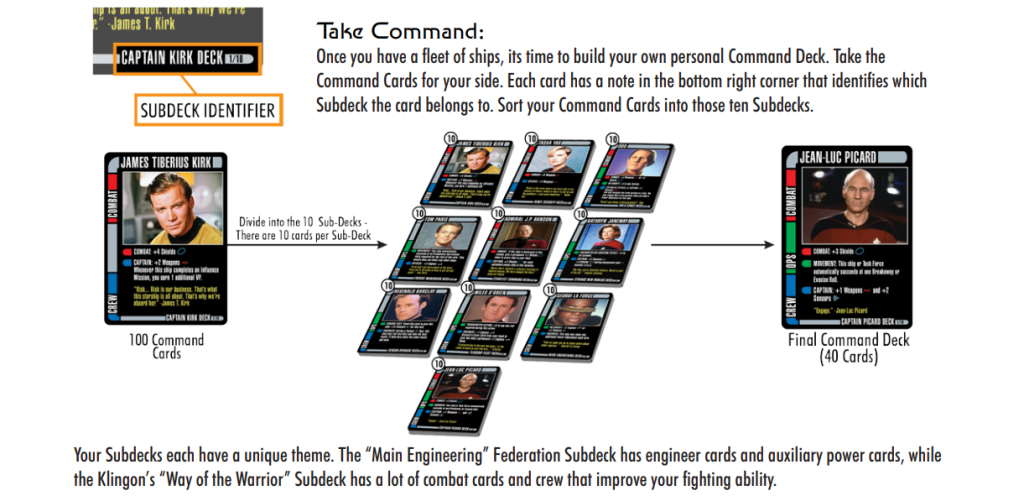

Set-based deckbuilding is also not restricted to digital deckbuilders either. While having small set sizes is fiddly enough that it probably needs to be digital (it’s hard to imagine keeping track of, say, a bunch of three card sets as you add and remove them from a deck of physical cards), there are tabletop games that use the mechanic, usually with larger set sizes. The three combinable heroes/factions you pick in David Sirlin’s Codex (2016) work this way, for instance. It’s also the main mechanic in Star Trek: Fleet Captains (2011), where each side comes with ten “sub-decks” of ten cards each, and you pick four of those to get your final 40 card deck.

This makes the game much more replayable and customizable (10 choose 4 means there are 210 different combinations of possible command decks), while making the deckbuilding phase only four decisions, instead of forty.

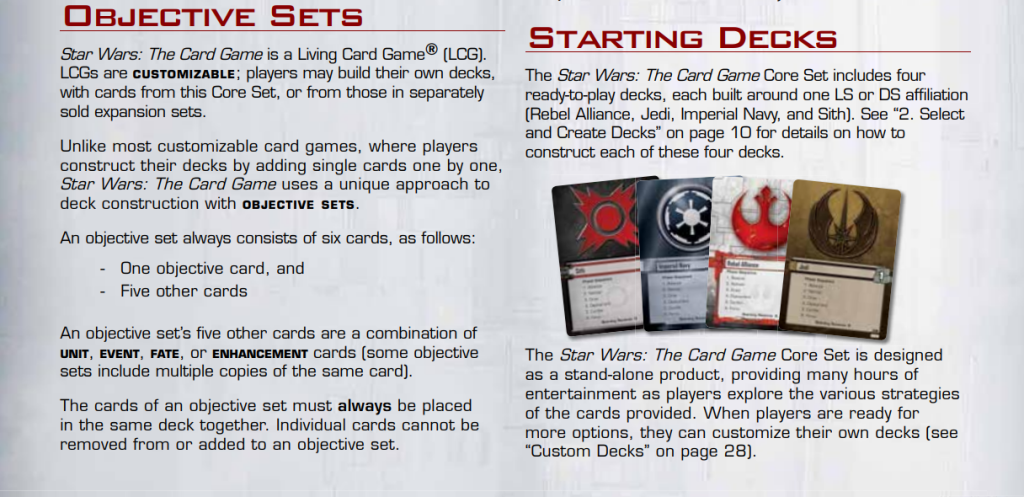

This idea of balancing interesting complexity is explicit in Star Wars: The Card Game (2012). The deckbuilding itself is broadly similar to the Star Trek Captains one (but with a deck assembled from 10 sets of 5 cards each). But interestingly it makes the set-based deckbuilding one of the game’s primary selling points:

This brand new model makes deck-building more accessible to new players, as they have only to select ten objective sets and combine them rather than assemble an entire deck, individual card by individual card.

This model also presents a compelling new deck-building challenge for veteran card players. Traditionally, veteran players approach customizable card games by evaluating the worth of every individual card in a deck. Star Wars: The Card Game, however, explores exciting new design territory; players are faced with the task of evaluating groups of cards and building a deck by selecting among those groups.

And has this idea front and center in the rules as well:

This is one of the only games I’m aware of that specifically highlights the presence of “set-based” deckbuilding as a key feature.

Affordances of Set-Based Deckbuilding

You can get a sense from the examples above of some of the ways set-based deckbuilding is similar to, but different than, singleton deckbuilding. Having it means:

- There are fewer decisions needed to make to assemble a deck, because you’re assembling some number of sets of cards, instead of card by card.

- While there are fewer decisions, the decisions themselves are more complex since there are potentially more cards to assess and compare.

- It enables synergistic or thematic groupings for the sets of cards. Because they don’t stand alone, the cards take on meaning contextually as a group. This allows for pre-built mini combos of cards, helping to ensure the player will have an interesting and working deck.

- As a result, it makes it much easier for the player to create interesting and distinctive decks, because they’re given working components to start with. This also means pruning and filtering mechanics aren’t really needed.

- The design can support more viable deck archetypes, because you have much more control over what the player will have and so more complex strategies can be supported.

- The designer is balancing sets of cards together, rather than balancing individual cards. This can make the task of balancing easier because it opens more options: A set can include one great card and two bad ones, or three mediocre cards. Tweaking a set might mean making a great card worse, or making bad cards better, or not tweaking cards at all and simply adjusting the set itself.

Again, this isn’t “better” or anything, it’s just different, and has different affordances.

I love the way that having a fixed set can completely change the context and meaning of similar or even the same cards. Like here are two sets from weapons for the hunter class in Card Quest, the composite bow versus a short bow:

In the top set, you’re meant to open with the “Precise Shot” cards: they’re powerful if played first, and get weaker and more expensive if played in a chain (chaining sequences of cards is one of the game’s primary mechanics). The normal “Shot” cards also lose strength when chained, but they get cheaper and also draw a card, so a good sequence is a “Precise Shot” for big damage, followed by weaker “Shot” cards that cycle your hand. But in the short bow set, we now have “Quick Shot” cards, which always draw, and only lose a bit of power when chained. Suddenly, “Shot” is now the strong opener we want to lead off with because of its damage, followed by plinking with the “Quick Shot”. It’s pretty minor, but I love this sort of nuance that can emerge because there’s only these two permutations available.

I think the ability to set up little synergies is especially helpful in making good use of the design space. In singleton deckbuilding, imagine a card like, “+2 to all woozles”. This card might be really good if the player already drafted some woozles, but useless otherwise. This is already sort of bad design, because it means it’s a win-more card if they’re already building that way, but unpickable otherwise, so it’s never an interesting choice. An easy decision like that can still be fun sometimes, but it sharply limits how many such cards you can have in the game, otherwise the player could get inundated with nothing but dead cards and too-obvious-picks. I think a lot of Slay the Spire-likes really fall victim to this particular design pitfall, and end up with many cards that essentially say, “If you are drafting woozles pick this, otherwise never choose it”, which is a bit boring and railroad-y.

But with sets, you can package the woozle boost alongside some woozles cards. So there’s some base level of functionality that prevents cards from ever being completely useless. But there’s still room to complicate it, by having other sets that further develop the synergy or accentuate it in a different way.

In a singleton deckbuilder, the player is finding individual parts and trying to assemble a working engine. In a set-based one, it’s more like they’re finding already working parts of a car, and trying to build one that’s fun to drive? Something like that.

As I’m thinking about it, I’m realizing that set-based deckbuilding really shifts the focus from building the deck to playing it. In a good singleton deckbuilder, the fun is in assembling this broken engine yourself piece by piece, making something that by the end is overpowered from all the synergies you’re exploiting. That ending deck might actually be a little boring to play, if you had to play it all game long. Or it might not work at all! But in a set-based deckbuilder, there’s still some fun in building the deck, but it’s really about piloting it in its finished state. This focus on the actual playing of it supports a different kind of complexity.

I’m realizing this points to another distinction- deckbuilders where you build during the game itself, versus this more ‘building phase’ that precedes the game approach. Are there terms for those?

Drafting Deckbuilding, vs Preconstruction

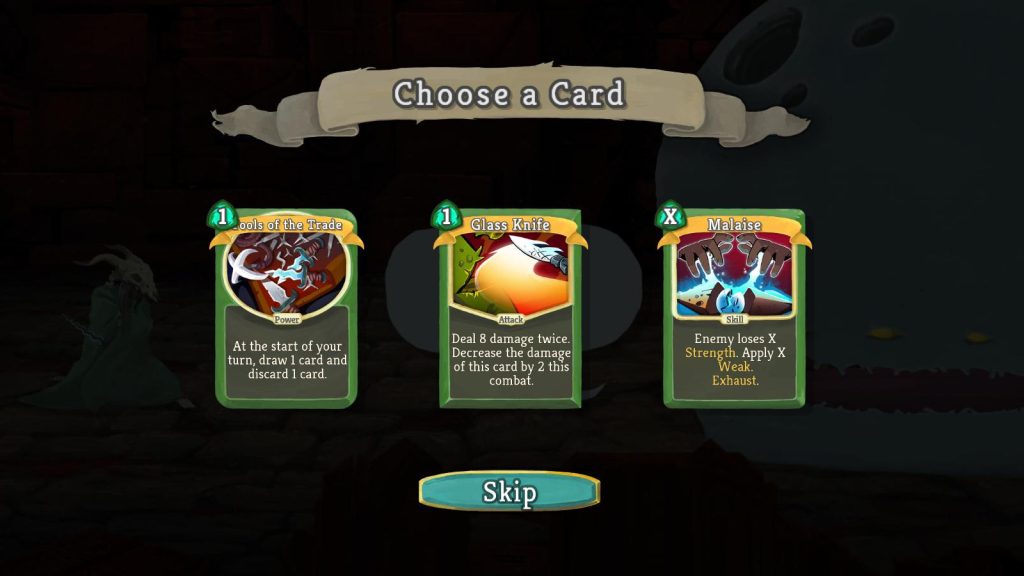

So let’s say also that most all deckbuilding games are about “drafting”, that is, you’re building your deck during primary gameplay. So in Slay the Spire (2017), you start with a small deck of cards, and then as you go you get various opportunities to add and remove cards from that deck. Most commonly, you’re most often presented with three cards and asked to select one to add to your deck:

(This is so canonical as a trope that in my Economics for Game Designers class this past spring, designer Olin Gao made a game prototype called Three Card Wonder that is just that decision, over and over, turning a deckbuilder into an incremental game. It’s pretty great).

There are various ways to select the cards, the key point is just adding or removing single cards as you build your deck, and doing that is the game. That’s how it works in Donald X. Vaccarino’s Dominion (2008), the deckbuilding genre definer. He was inspired by drafting in Magic: The Gathering (1993) and especially a digital MtG game often called Shandalar (1997). In Magic, drafting as a mode of play distinguished it from the standard formats where decks are built beforehand. I think all this terminology is useful, so let’s say “drafting deckbuilders” for this standard form of the genre. Building the deck on the fly in this way is different than when the deck construction takes place entirely before the game occurs, like in standard “preconstructed” Magic. So we could call the prebuilding a “preconstructed deckbuilder” I guess. But is that just a regular card game at that point?

No, I don’t think so, there is something different about having a focus on deckbuilding that’s different than a game that uses cards and you can build the deck. I think this distinction is awfully fuzzy in practice, especially among digital games. But there are some games that don’t feel like deckbuilders, even though they technically having you modifying a deck over time, and there are some deckbuilders that do feel like deckbuilders, even though you don’t modify the deck during a run. So like, I think it’s useful to consider Aces & Adventures (2023) as a deckbuilder, even though the deck is built during ‘preconstruction’, and Card City Nights (2014) isn’t a deckbuilder, even though you’re adding and removing cards across the whole game. It’s weird.

Drafting or Preconstructed in Singleton or Set-Based Deckbuilders

Anyway, I don’t need a formal definition, which is always a fool’s errand anyway. But I think it is helpful to have these groupings. Because given all the above, we can see that “singleton” deckbuilding is a good choice if the game is about deckbuilding, where the focus is on constructing a tight engine over the course of a game, so a “drafting” deckbuilder specifically. But it’s maybe a poorer choice if the deckbuilding being used as a source of randomness in support of other systems, and actually using a set-based approach might be better in those cases.

I think the “set-based” approach is rare simply because there aren’t that many examples and none have been runaway successes yet. But it ought to be a more common part of the palette of these games I think. A lot of games that are doing “Slay the Spire, but with X”, especially when X is tactics/RPG gameplay, might really benefit from the affordances of designing for sets!

Leave a Reply